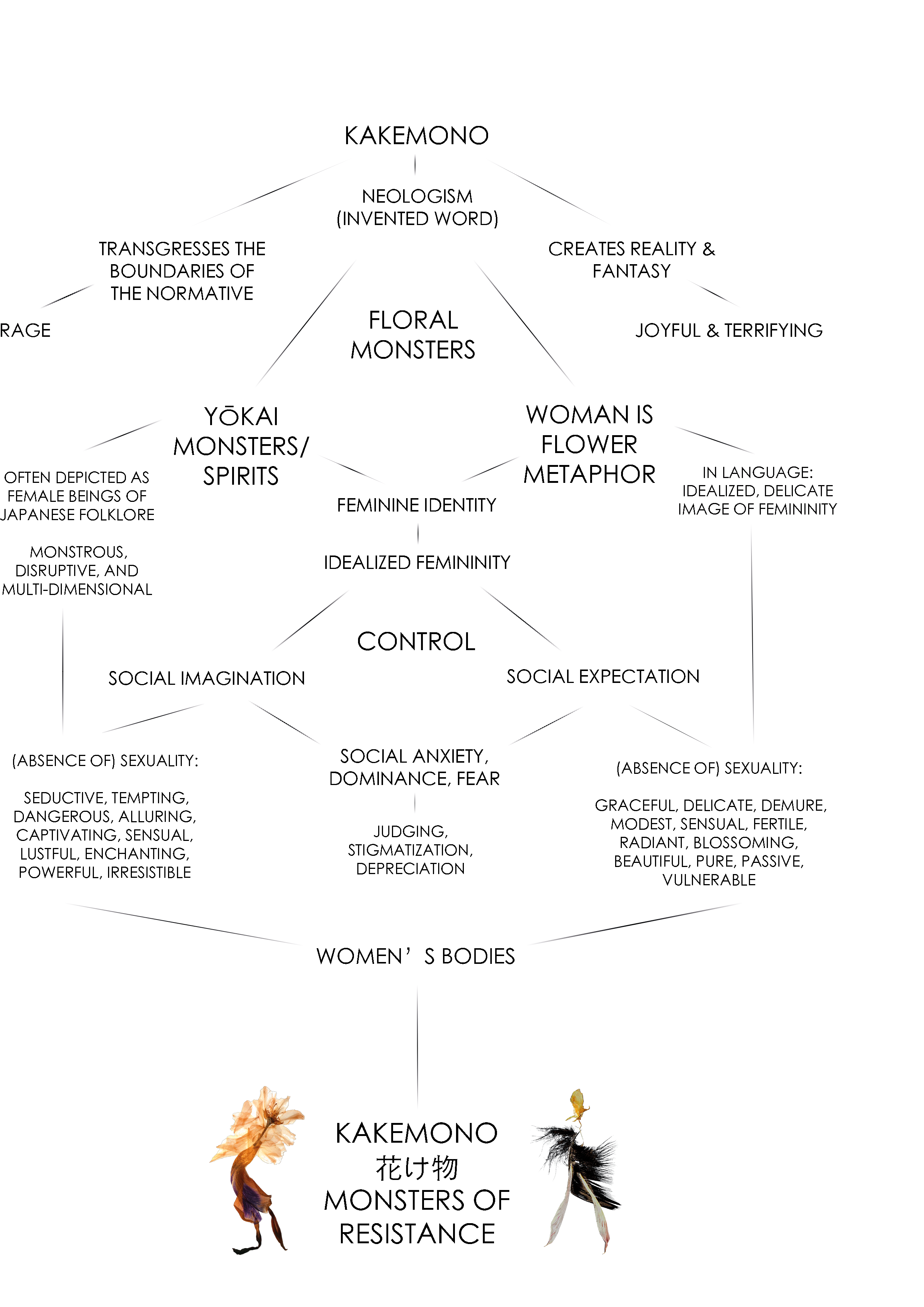

This concept begins with the metaphor WOMAN IS FLOWER—an idealized, delicate image that I felt is oversimplified and confines the complexity of femininity. I felt like yōkai—the transforming and monstrous beings of Japanese folklore offered the perfect framework to break free from this fragile metaphor. Many of the most powerful and transformative yōkai are female figures, often monstrous, disruptive, and multi-dimensional. I began to collect and “arrange” flowers in a way that would evoke kakemono figures – my own invented group of yōkai, creating a tension where both WOMAN IS FLOWER and the yōkai challenge each other, neither fully conforming to the typical, rigid definitions of monstrosity nor femininity.

Kakemono 花け物 (花 hana, ka = flower; け物 kemono = monster) is a neologism, a concept where metaphor and reality intertwine. It lies at the intersection of the metaphor WOMAN IS FLOWER and yōkai folklore, particularly drawing from the name of the shapeshifting bakemono tradition (化け物, where 化 ba = change, and け物 kemono = monster), blending the idealized image of femininity with its deeper, more “monstrous” reality.

Yōkai spirits include:

- Bakemono: Shape-shifting creatures

- Yūrei: Ghost-like spirits, often vengeful

- Tsukumogami: Everyday objects that gain spirits after 100 years

- Kaiju: Massive, destructive monsters, embodying chaos

- Kakemono: Flower-like monsters, shifting femininity

In their context, yōkai beings manifest societal anxieties and cultural constructs. The prevalence of female yōkai, often outnumbering their male counterparts, reveals a troubling societal paradigm steeped in the subjugation of women. Heian and Muromachi periods (794-1392) frequently depicted mistreated women as vengeful ghosts, reflecting cultural fears and social anxieties surrounding female sexuality and reinforcing the connection between the supernatural and societal anxieties about women’s bodies.

Kakemono challenges the delicate metaphor that confines femininity to narrow definitions, instead embracing a “monstrous” and evolving identity. It also challenges the very concept of yōkai by subverting the expectations of monstrosity within the folklore itself, creating a space where femininity and monstrosity are not mutually exclusive but exist in a fluid, dynamic relationship. This pushes against traditional definitions, opening up new possibilities for reading both the feminine and the monstrous, as both categories become more complex and less confined by their typical roles.

Eventually, I met Zack Wood, an artist in Kyoto, who integrates divination into his art practice. I reached out to him to help bring these ideas to life through a deck of cards—one that encourages breaking free from limiting metaphors.

For the third edition of betweenanxietyandhope.me, we set out to create a deck featuring kakemono characters. Zack focused on interpreting their meanings in a divination reading, while I developed their backstories as flower monsters. We worked independently, not sharing our ideas until the final moment of combining them.

In many ways, my kakemono stories embody my own memories—emotions, desires, and fragmented moments. They reflect the “monstrous” aspects of my life, seen in my decisions, experiences, and fleeting moments of uncertainty. They take shape from the same flowers I once bought to decorate my room or picked up during long walks to clear my head. They are also born from random notes I wrote on my phone, often without knowing when or why they appeared.

My flower monsters resist rigid definitions. Shaped by personal histories rather than fixed archetypes, they dwell in spaces often overlooked, feared, or deemed unclean—catacombs, swamps, the forgotten edges of the world and the mind. These places, marked by mystery and decay, are where they find life and meaning. Rather than symbols of fear, they embody transformation, thriving in the margins where new possibilities take root. My monsters—and this is where they align with Zack’s—are not meant to be tamed or categorized. They exist on their own terms, flourishing in hidden spaces, carrying the weight of memory, and embracing the beauty of what is misunderstood.

In contrast, or comparison, Zack’s monsters are playful and full of life, often depicted swaying happily in forests or fields. While still capable of danger, they embody a sense of joy and spontaneity rather than fear. Zack approaches monsters with a belief that they should be fluid and evolving, not rigid or confined to the traditional forms often imagined, defined, and disseminated by straight Japanese men at the center of society. For Zack, monsters lurk in the margins, emerging from the unknown to challenge societal norms. They embody possibilities beyond established conventions—more about freedom than fear. They celebrate their monstrosity, transformation, and the fluidity of identity. At the heart of Zack’s approach is to allow the monsters to be themselves, unlike traditional “monster guidebooks”—which often frame creatures as things to be captured, befriended, or defeated. While one might have a meaningful interaction with them, they are not here for human control. His monsters as well exist on their own terms, reveling in their independence as much as in their ever-shifting forms.

Though our monsters manifest differently, our stories surprisingly align. This contrast, along with the shared underlying themes, became a central reflection in the deck. We decided that a card’s meaning would shift depending on whether it was face-up or face-down, capturing the duality of human experience. Some monsters lean toward the cheerful, while others are more somber—yet neither fully conforms to rigid definitions of monstrosity, femininity, or monstrous femininity.

The first line of the website, when face-up, aligns with monsters as liberating, fluid, and evolving forces, while the face-down, horizontal line intensifies this with a more subversive, destabilizing energy. These two lines coexist as part of a single, fluid continuum, where a kakemono can be both joyful and terrifying, both liberating and unsettling because the monstrosity itself is both a source of power and a marker of resistance.

I don’t miss summer in this snowy country. 雪の国では、

But I would join forces— 夏が恋しいとは思わない。

from my window, けれど、窓から

a cooperative effort, calculated risk, 協力し、計算されたリスクを取り、

and copious sake— たっぷりの酒と共に

to awaken the street yokai 街の妖怪たちを目覚めさせる。

hidden in the frost, 氷の中に隠れ、

waiting, watching. じっと待ち、見守る彼ら。

Will they bring good luck 今年の雪の季節、

to the quiet streets 静かな街に

this snowy season? 福をもたらしてくれるだろうか。